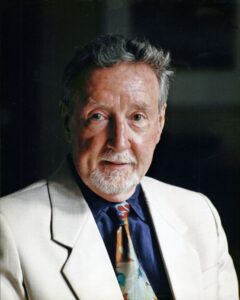

On October 11, 2022, David Flaherty passed away in Victoria BC at age 82. He was born on February 25, 1940, in Campbellton, NB and raised in Montreal, QC. Having received the gold medal in history from McGill University, he received his doctorate in history from Columbia University. He went on to teach American history at Princeton University and the University of Virginia before returning to Canada, where he was appointed in the law and history faculties at the University of Western Ontario. In 1992, he was appointed as British Columbia’s first Information and Privacy Commissioner.

Since his death, generous tributes have been offered by the many friends and colleagues whose lives he influenced and touched. He was a well-known philanthropist, and a generous donor to many arts and community organizations. And for privacy scholars, advocates and professionals he was known for his pioneering work on privacy protection, his impact as British Columbia’s first Information and Privacy Commissioner from 1992-1999, and his work as a principled privacy consultant to many organizations in the public and private sectors.

At the recent Vancouver International Privacy and Security Summit, I had the privilege of organizing and chairing a panel on David Flaherty’s contributions to privacy protection. His three main successors, David Loukidelis (1999-2010), Elizabeth Denham (2010-2016) and Michael McEvoy (2018-present), joined me to discuss his work and his legacies. The panel allowed us to reflect on the role of the contemporary privacy or data protection agency, and to draw lessons from Flaherty’s extraordinary work and example. The fascinating and wide-ranging discussion emphasised how influential his work has been, in Canada and globally, and how it remains relevant even though digital technologies and organizational practices are so dramatically different from when he first wrote about the subject back in the 1970s.

Perhaps David Flaherty’s most influential work was his 1989 volume, Protecting Privacy in Surveillance Societies based on extensive documentary analysis and interviews in the U.S. Canada, West Germany, Sweden and France. He had the opportunity to draw upon his academic research when he took up the job of BC’s first Information and Privacy Commissioner in 1992.

However, his appointment was not universally welcomed. He was an academic, who had never lived in BC, and was travelling directly from a sabbatical leave in Washington DC. This was a resume that was not likely to endear him to the practical and down-to-earth approaches of public servants in the west of Canada. He also had a very new law to implement and enforce. The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act of 1992, combining (on the Canadian model) both access to information rights with privacy rights, was a real innovation that was going to alter radically the life and work of BC public bodies. He therefore had a blank slate, and an opportunity to give the law a life that could endure. He wrote 320 orders over the 6 years he was in office.

He was, in retrospect, the perfect choice as BC’s first Commissioner. He had a massive international profile, an extensive network of contacts, a huge level of self-confidence, and a reputation that could not be equalled by anybody in the province. His voice counted because of that experience. And it was not just his academic experience, because since 1973 he had been advising organizations on privacy rights and compliance through his personal consulting company. He also continued to hold a tenured Professorial position at the University of Western Ontario throughout his time in office. He had no ambition for advancement within the BC public service. He knew, and the government knew, that he offered a truly independent voice.

His three successors reflected on Flaherty’s style as a commissioner. He had the larger perspective on the effects of information technologies on privacy rights, but he was also practical and down-to-earth. He was conciliatory, respectful and consensual when he needed to be. But he was also not afraid to be provocative and to speak out in the media when the circumstances warranted. He was very skilled at keeping the government off balance. And he was very good at voicing that appealing soundbite to justify his actions. He was skilled at explaining the values of privacy in everyday language, and with practical accessible examples that ordinary citizens could easily grasp.

Although he had no training as a lawyer, as a historian of the law he fully understood the basic principles of statutory and constitutional interpretation, and the intricacies of the judicial process. At the same time, he remained an unapologetic privacy advocate and was ready to push the boundaries of the law, especially in his investigation reports, when he believed it necessary. He was often impatient with the “black letter of the law” and keen to advance a just outcome keeping in mind the central purposes of the legislation. But he was also conscious of the constraints imposed by the possibility of judicial review, by his limited budget, and by the administrative and political culture within which he operated.

Throughout his tenure, David Flaherty skillfully reconciled the various roles of the contemporary privacy commissioner that Charles Raab and I discussed in The Governance of Privacy– ombudsman, consultant, educator, adviser, negotiator, enforcer and auditor. It is a tough job that requires adaptability, intelligence, hard work, but also an enduring an unwavering commitment to the essential principles underlying information rights.

His work as an “auditor” is worth some special mention. His scholarship on the early data protection laws was very complimentary of the work of the German data protection authorities because they had instituted early and comprehensive auditing programs. He did not conduct many formal audits of public bodies during his tenure. But he did believe in the more informal approach of “site visits.” He would write to a hospital, for example, and announce that he wanted to visit and understand their personal data handling practices. On these visits, he would then point out some obvious shortcomings – the file folders in the corner of the office, the personal information scrawled on the white board, the passwords written on sticky notes and pinned on computer terminals. After a while, news of a “Flaherty site visit” would make public servants nervous, and prompt feverish efforts to improve security for fear that they would attract the Commissioner’s wrath. At the same time, he was always ready to praise individuals and organizations whom he thought were doing a good job. Through these visits he was able to instill cultures of compliance, and enhance the profile of the Commissioner and of his office.

Although he was often deliberately unpredictable to keep government on its toes, David Flaherty was also very principled. The fair information principles were, and remained, his central guiding model throughout his entire career as a privacy professional. In his chapter in a book that I co-edited following a very successful international conference in 1996, he wrote: “Based on my experience in doing research and writing about data protection issues and in five years of direct experience as a privacy commissioner, I have never met a privacy issue that could not be satisfactorily addressed by the application of fair information principles, broadly defined.” He believed that throughout his later career as a consultant – as new generations of digital technologies came and went, and as new online business models overwhelmed our lives. His historical training and sensibilities produced a strong belief in the enduring value of privacy rooted in the human experience, and a profound belief that privacy was far more than a legal or technological question. This perspective was informed by his early PhD work on Privacy in Colonial New England (University Press of Virginia, 1972).

As an academic and as a regulator he was always focussed on the empirical and the practical. He had little tolerance for some of the more abstract social theorizing about surveillance and the networked societies. At the same time, he had an extraordinary ability to cut to the heart of an issue, and to see the bigger conflicts and questions. This inspired him on regular occasions to warn his successors to “not go down every rabbit hole.” By this, he was stressing the importance for any regulator to pick his/her battles carefully, and to choose those that would genuinely advance the cause in a very practical sense.

His academic background also motivated a very horizontal management structure in his office, not unlike that of a university department. He hired some of the very best staff, many of whom continued in productive careers in information policy. He was conscious of resource constraints, and strived to choose the very best people, and to give them full rein to implement the law. So, when David Loukidelis took over the role in 1999, he found a highly efficient and motivated team that could support the transition.

David Flaherty was also very ready to invite speakers (from many walks of life) to his office to discuss privacy developments in Canada, and overseas. He believed very strongly that the work of his office – the interpretation of the law, the investigation of complaints, the mediation of disputes, the advancement of the cause, could and should be influenced by the learning and experience of others in the field. And he did his very best to take advantage of any opportunity to expose the office staff to individuals from his huge network of experts who happened to be travelling to British Columbia.

What is more extraordinary, however, is the fact that he managed to advance this important cause in three professional capacities – as an academic, as a regulator and subsequently as a consultant. I know of no other scholar who has demonstrated such professional versatility. Only his innate intelligence, his extraordinary capacity for hard work, his sharp wit, his unrivalled ability to cut to the chase on any issue and his unwavering commitment to privacy as an essential human right, permitted this professional transformation.

David Flaherty was a fine writer, a brilliant conversationalist, an engaging public speaker at countless international conferences, a lover of all the arts, a philanthropist, and an insatiable reader. In an era of excessive specialization, he was a quintessential “renaissance man” who displayed an insatiable love of life and learning. Contemporary privacy professionals have perhaps become too specialized. David Flaherty’s career stands as a reminder that the study of privacy is inherently interdisciplinary and can only be fully appreciated if one understands its full historical, philosophical, political, and social dimensions. His career stands as testament to the central principle that law and technology should serve human interests and rights – and not the other way around.

A version of this article appears in Privacy Laws and Business International Report, April 2023. www.privacylaws.com