It is tempting to conclude that what happened in the presidential election last Tuesday was not only a repudiation of the ‘Washington establishment’ and the mainstream media, but also of the use of Big Data in elections. Perhaps people are sick of being considered ‘data points’ in an endless struggle to manipulate their political attitudes and behavior.

Among other things, maybe the Trump victory represented a rejection of the kind of elitist attitude of high-tech consultants that voters are just data points who can be influenced if you know enough about them, and give them the right sales pitch.

I have written about, and critiqued, the assumptions behind data-driven elections for some time. The massive accumulation of personal data in voter management systems, the micro-targeting of increasingly precise segments of the electorate and the construction of increasingly personalized (and private) ads on social media constitutes a pernicious, and largely unregulated, form of surveillance. The practices pioneered in the US are creeping into other democratic countries, including Canada. They are having a troubling effect on our privacy, our civil liberties and our democracy.

Some were very quick to slam the ineffectiveness of Big Data modeling last Tuesday. Republican consultant Mike Murphy tweeted, I’ve believed in data for 30 years in politics and data died tonight. I could not have been more wrong about this election.

Big Data blew it Tuesday asserted an article in the Wall Street Journal.

It is generally agreed that the Democrats had a huge advantage in data analytics. Supporting the Democratic machine is a giant campaign technology infrastructure of data brokers, data analytics and marketing companies. Increasingly integrated, the data drives all campaign messaging decisions: on the doorstep, on TV, in rallies, and through social media.

According to Jim Messina, Obama’s campaign manager in 2012, Big Data is outdated, because campaigns have entered the era of little data. He wrote a week before the election: Today, campaigns can target voters so well that they can personalize conversations. That is the only way, when any candidate asks about the state of the race, to offer a true assessment….Hillary Clinton can do that. To my knowledge, Donald J. Trump, who has bragged that he doesn’t care about data in campaigns, can’t.

And the NGP VAN company which provides the platform for the massive Democratic voter file now boasts about being able to construct a single profile of the unified voter from its data, so that the campaign does not just see a person in terms of crude demographic categories, but as a complete person, to whom personalized and strategic communications can be directed. A fine book by Daniel Kreiss called Prototype Politics (pp. 214-5) analyzes and critiques these trends. Kreiss also points out how these assumptions also fuelled the politics of “personal attachment” that characterized the old political machines like Tammany Hall in New York.

By contrast, Trump was quoted in the Spring as saying that he thought the impact of Big Data was exaggerated: Obama got the votes much more so than his data-processing machine. And I think the same is true with me.

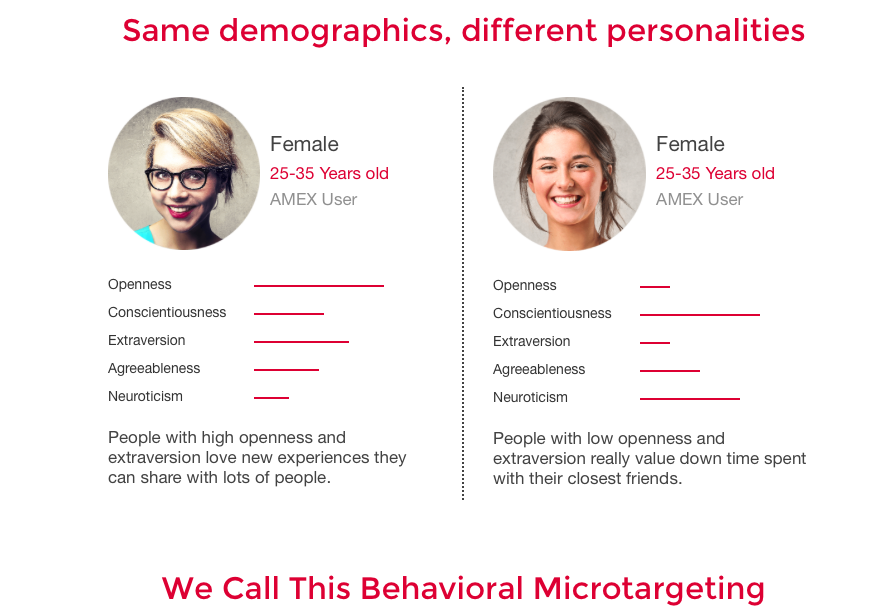

And then it was reported that he had contracted with a UK company, Cambridge Analytica, prominent in the Leave campaign in Britain. The company boasts a data file of over 200 million US voters, and also engages in the controversial practice of psychographic profiling adding personality traits to traditional demographic and consumer categories.

So, despite his initial skepticism, Trump did have a digital operation, based in San Antonio, engaged in extensive fundraising and social media outreach. According to initial reports, the data were driving Trump’s messaging and the decisions about where to send him including to states like Michigan and Wisconsin, which in the end proved pivotal.

Data science can also be used to identify and get out your vote. But it can also suppress the vote of your opponents. According to the same article the Trump campaign reportedly had three targets: idealistic white liberals (pro-Saunders and against trade deals); young women (who needed to reminded of Bill Clinton’s philandering); and African Americans (reminded in Facebook posts of Hillary’s alleged 1996 comments about black youth being ‘super-predators’).

And Trump also relied on the extensive database and digital operation of the Republican National Committee in which there had been significant investment since the Romney loss in 2012.

So both campaigns had data loads of it. And both parties used it to get out their vote, and suppress that of their opponents.

We won’t know until serious research is done whether the Trump campaign’s assumptions about the profile of the electorate in 2016 were more reliable. There have already been some self-serving I told you so claims by members of the Trump team.

Data’s alive and kicking. It’s just how you use it and how you buck normal political trends to understand your data said Matt Oczkowski, head of Cambridge Analytica the day after.

He is correct; the data is only as good as the assumptions that drive the statistical models. And it is those models that dictate the voters that campaigns try to contact, how and with what techniques. And there will continue to be claims and counterclaims about what went wrong for the Democrats; not enough data? poor data integration? bad modeling? human fallibility?

And no doubt this analysis will lead to more data accumulation and a further drive to use data science to model and predict our behavior. The conventional wisdom is that data makes a difference at the margins. And in a close election, it did, and will continue to, matter.

So this will not be the last data driven election, either in the US or in Canada. And the Trump campaign did not reject the data driven approach in favour of old-style movement politics with his mass rallies. So let’s not get too carried away with the notion that Trump won because he successfully mobilized a huge populist movement against political and media elites.

On the other hand, it would be very nice if the many proponents of the data-driven election took a step back from this election, and asked not how they can improve their tools, not how they can accumulate more data, not how they can strive for the more perfect view of the ‘unified voter’ but whether these practices aren’t in fact totally counter-productive, and fundamentally anti-democratic. The massive “data ecosystems” that surround modern American political campaigns constitute an unregulated surveillance system that does little to enhance American democracy and much to turn off voters.

Hillary had more, and better, data on the US electorate at her disposal. It failed her. And it will continue to fail. I disagree with virtually everything Trump says and stands for. But on this, he may be right. The impact of Big Data on elections is overrated.